History of the Cobalt Ontario Mining Camp

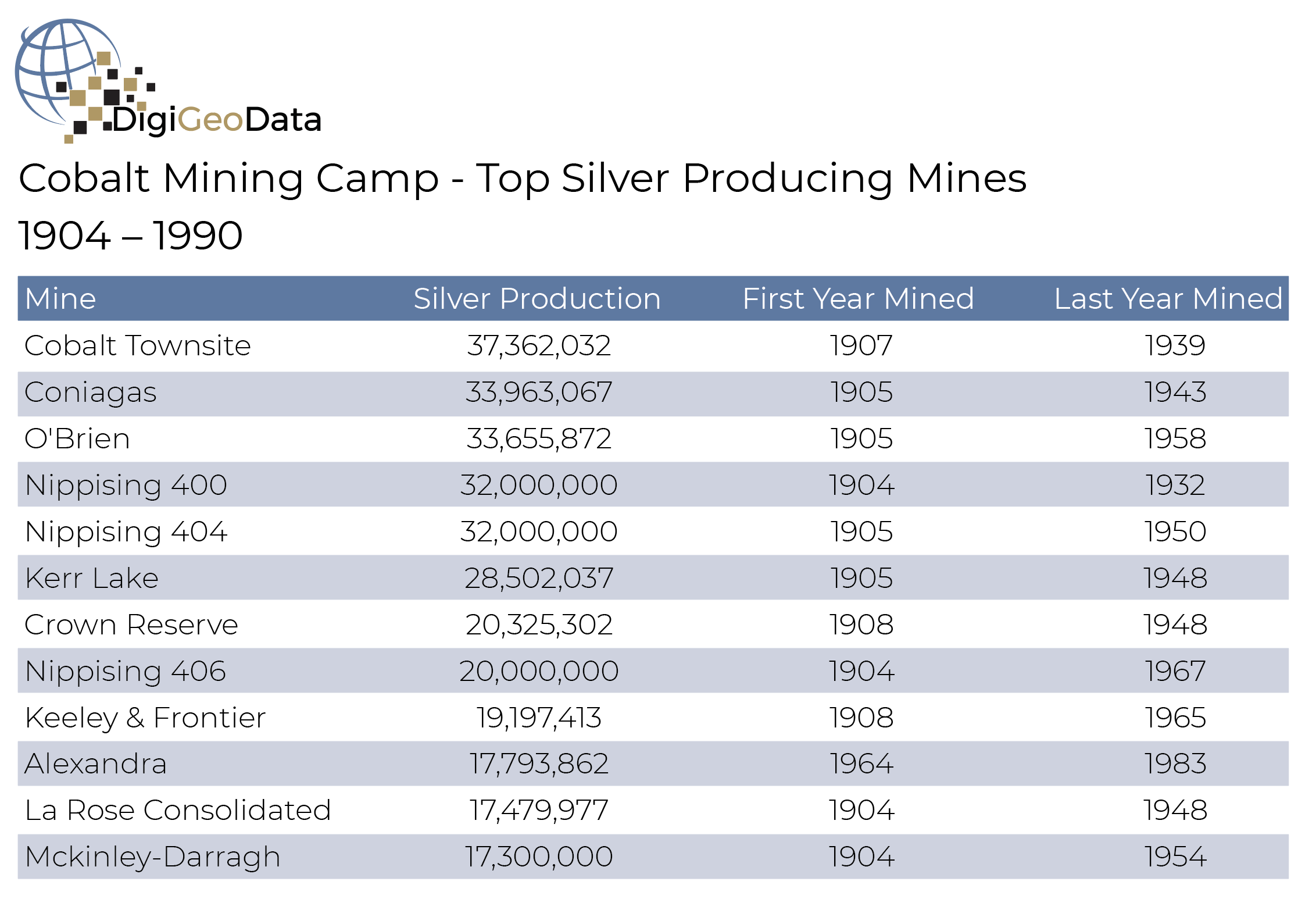

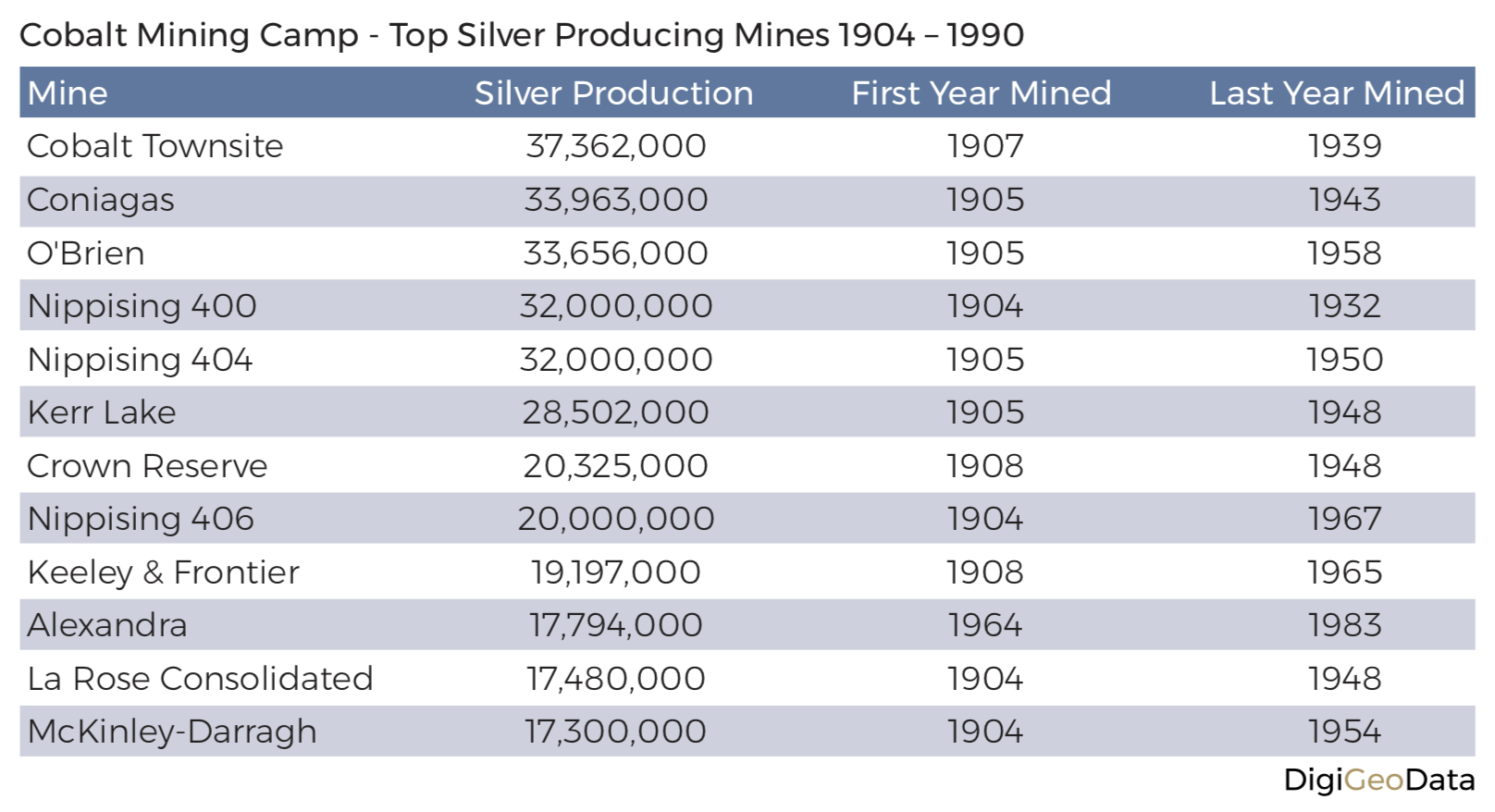

Silver was first discovered at the southeast end of Cobalt Lake in Ontario in 1903 by James J. McKinley and Ernest Darragh, who working on the new Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway. They noticed metal in a road cut, staked a claim, and sent samples for assaying. The samples returned values of over 4000 ouncers of silver per ton. This claim became the McKinley-Darragh mine which started production in 1904 and produced over 17 million ounces of silver until it closed in 1954.

This was the beginning of the great Cobalt Silver Rush.

At the end of 1904, there were already 6 producing mines. This increased to 21 operating mines by the end of 1905.

At the peak of production, there were more than 100 operating mines and 18 mills supported by a population of 12,000 people.

By 1910, the Ragged Chutes Compressed Air Plant supplied compressed air to the area mines through an extensive network of pipes, some which can still be seen today.

Silver production peaked in 1911 with production of 31,500,000 ounces. By 1922, more than 333 million ounces of silver had been produced.

The Cobalt Silver Rush lasted into the 1930’s. By 1932 only one mine remained open. Immediately after the war, cobalt became a valuable mineral and several mines re-opened.

There was a brief resurgence in the 1950’s which lasted into the early 1970’s. Several mines continued to produce with the last two mines, the Beaver and Langis, closing in 1989.

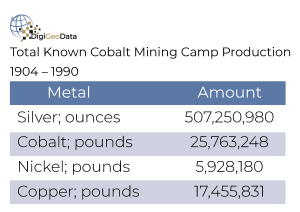

Although silver was the metal of choice, it was not the only metal produced from this area. There was a significant amount of cobalt and nickel and copper as evidenced in the production table.

The town of Cobalt was named by Willet Green Miller, Ontario’s first Provincial Geologist. While visiting the area in October of 1903, Miller set up a crudely lettered board which read “Cobalt Station T. & N.O. Railway”.

During his visit that year, Miller interacted with many of the prospectors, helping them to identify silver in the rocks. The following year he headed a full-scale geological survey party which resulted in a significant and optimistic report for this new mining camp. In his report he spoke of “pieces of native silver as big as stove lids or cannon balls lying on the ground, as well as cobalt bloom and niccolite.”

Silver was produced mainly from veins with impressive metal content, some up to 10 feet wide and assaying over 4200 ounces per ton.

In a sense Cobalt has always been a “poor man’s mining camp”. Because most of the rich mineral-bearing veins lie close to the surface, very deep mines and costly operations have never been necessary. Generally, the individual mines were not large or elaborate operations compared to those found in other areas of Northern Ontario. The ore was significantly rich and plentiful that large operations were not required.

Many miners and prospectors learned their trade in Cobalt, and then moved on to other discoveries in Kirkland Lake, Timmins and elsewhere. The hundred or so of relatively small mines developed early in Cobalt’s history were consolidated over the years into bigger mining companies that went on to develop other mines.

Cobalt is one of only 3 mining camps in Canada—Dawson City in Yukon and Barkerville in British Columbia are the others—to be designated as a National Historic Site.

All the early exploration and mining has earned Cobalt the distinction of being Ontario’s most historic town.

Today it is not silver that is causing the return to the town and area around Cobalt. It is the metal that the town is named after, Cobalt.

There has been a resurgence of interest in the area. Exploration companies have returned to re-evaluate many of the properties and past producing mines.

Cobalt has recently become a metal of interest for many reasons, but the main interest is for use in rechargeable batteries in electric cars. Cobalt is used in 3 of the 5 common battery chemistries used in the lithium-ion battery market.

Companies are exploring for a more secure and local supply of Cobalt as more than 50% of the global cobalt in-situ reserves are in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in Africa. In 2016 approximately 65% of global cobalt production came from the DRC.

Will this renewed interest in exploration once again transform the town of Cobalt?